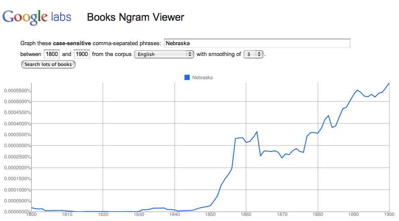

On Wednesday evening, October 5th, over 400 patrons of the humanities gathered at the Joslyn Museum of Art in Omaha, Nebraska, for the 16th Annual Governor’s Lecture in the Humanities fundraiser. Eric Foner, author of The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, gave this year’s lecture. The lecture was fantastic. Foner is one of the leading historians of 19th century America, and his book won the Pulitzer, Bancroft, and Lincoln prizes. His other works (Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War and Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution) stand as some of the most influential and widely-cited books in American history.

The evening was a smash hit for the humanities. As a fundraiser for the Nebraska Humanities Council, the event exceeded its ambitious dollar goals and broke previous fundraising records. President of the University of Nebraska J. B. Milliken warmly welcomed guests and opened the evening’s program. Governor Dave Heineman introduced the speaker.

Eric Foner opened his lecture with a recent inquiry he received from a film producer asking if it were plausible to include a scene with Lincoln–pause for effect–playing the harmonica. Then there is always Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. This set the tone for the evening: humor was allowed, sharp and interesting discussion would be celebrated, and serious questions about our past and the human condition would be undertaken. I had the opportunity to moderate the question and answer period after the lecture.

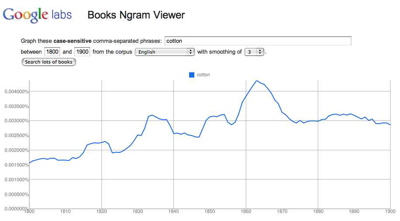

Several highlights from the lecture stand out to me days later. One was Eric Foner’s insistence on addressing the problem of “American” slavery. He drove home the point that much of the North was deeply complicit in the institution of slavery, that cotton’s wealth permeated, indeed underpinned, the Northern economy, and that New York City, in particular, benefitted so directly from slavery that it could hardly conceive of interfering with the institution. The breadth and reach of slavery is often missed or forgotten. Foner’s point, that slavery cannot be understood as geographically restricted to the South, has broad implications for how the American public today understands the coming of the Civil War.

At a student event earlier in the day, Eric indicated why the war was not caused by tariffs or economic policy (a common perception still) but instead caused by the problem of American slavery. The idea behind the tariff argument suggests that Lincoln was a representative of the bourgeoisie class in a battle with the South’s agrarian class, but this makes little sense. “600,000 Americans, I assure you, did not kill each other over the tariff,” Foner quipped. Both the North and the South were largely agrarian societies and both political parties and regions had bourgeois elements. The idea persists, but Foner directs our gaze to “American” slavery broadly construed, and the causes of the Civil War come into clearer focus.

A second highlight was Foner’s insistence on tracing Lincoln’s views on race and slavery to reliable sources. After Lincoln’s death, Foner points out, a whole host of recollections came forward claiming that Lincoln said this or that–that he was always against slavery, that he was born with a pen in hand to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. The historian needs to evaluate each of these with great care. Direct quotes attributed to Lincoln twenty, thirty, or fifty years after the fact are common. Piecing together Lincoln’s earliest views on slavery requires detailed assessment of the source–who reported it, when, and for what audiences. History depends on evidence and on assessing the evidence rigorously and carefully; we cannot just say what we want about the past. So, the art of history, Foner tells us, is to write from the evidence and, at the same time, to interpret it faithfully and reasonably.

A final question of the evening asked Eric Foner to explain what we can learn from Lincoln’s political development, from his capacity to grow. Here, Foner’s study of Lincoln holds up the importance of understanding as clearly as we can how politics, the human experience, and history broadly are intertwined. Lincoln, he said, had principles and convictions–most prominently against the institution of slavery–but he negotiated these in everyday encounters as he met with people, listened to them carefully, and reconsidered his positions. Intellectually curious and attuned to the subtle changes in public opinion, Lincoln’s capacity to grow came, Foner tells us, from his willingness to take seriously the views of his opponents, to adjust to and shape public opinion, and yet to hold fast to principles. Foner shows us in detail how politics operates in a democratic society, how an especially astute political leader changes over time and in relation to events and people around him or her. It is an inspiring and humbling lesson.

The Nebraska Humanities Council lecture turned into a major celebration this year, affirming just how many people value and support the humanities. And showing how much history and the humanities have to teach us today.