The Atlanta Campaign of 1864

- Railroad Junctions in the Atlanta Campaign, 1861

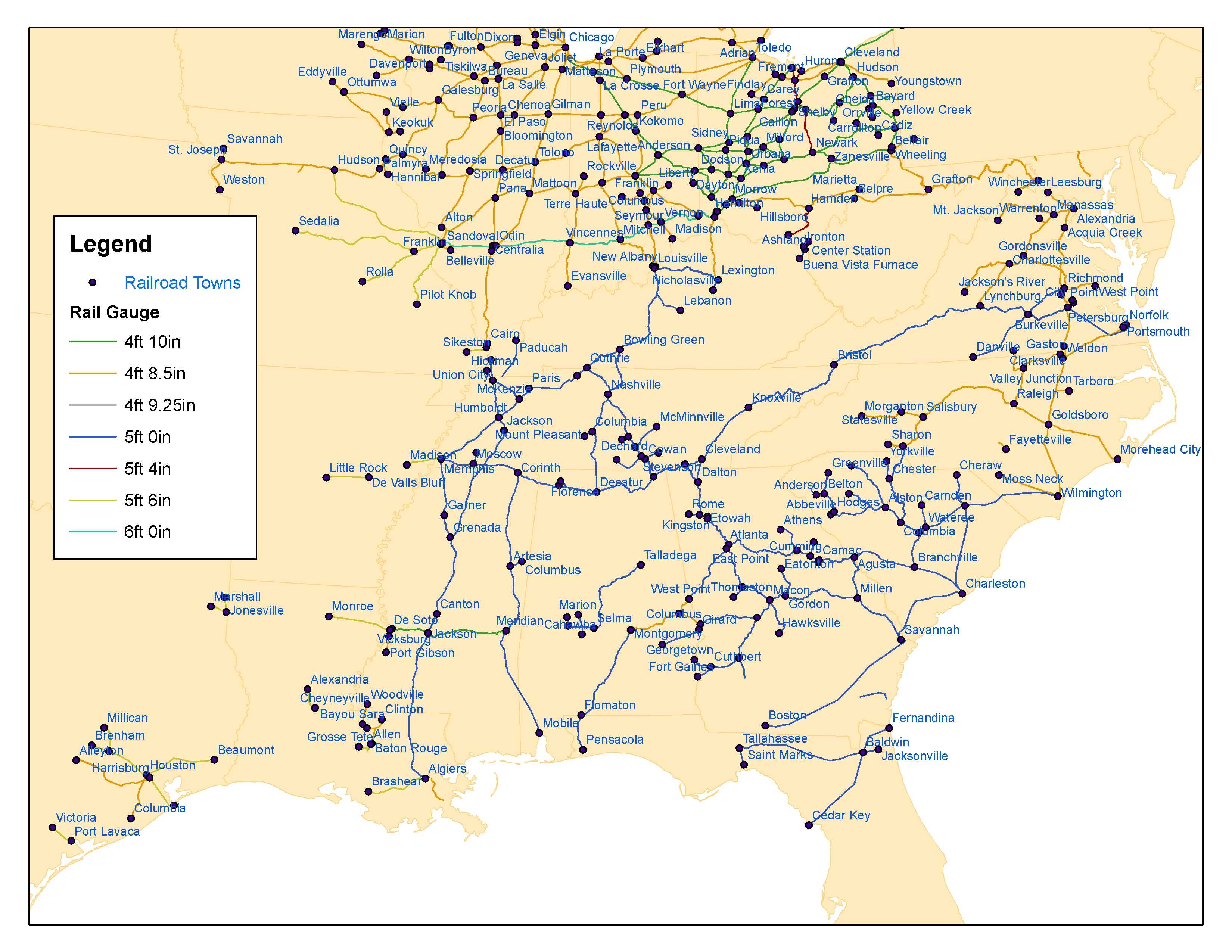

- Railroad Gauges in 1861

- Place, Time, and Organization Name View of the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion's Atlanta Campaign

- Word Cloud of Official Correspondence of William T. Sherman during the Atlanta Campaign

- Word Cloud of All Union Commander's Official Correspondence in the Atlanta Campaign

- Verbs paired with "railroad" in William T. Sherman's Official Correspondence, May 1864

- Verbs paired with "railroad" in William T. Sherman's Official Correspondence, June 1864

- Verbs paired with "railroad" in William T. Sherman's Official Correspondence, July 1864

- Verbs paired with "railroad" in William T. Sherman's Official Correspondence, August 1864

- Verbs paired with "railroad" in William T. Sherman's Official Correspondence, September 1864

- Concordance of all "railroad" terms in 1862 Peninsular Campaign Official Records

- Concordance of all "railroad" terms in 1864 Atlanta Campaign Official Records

Railroad Gauges in 1861

The standard interpretation of the way the rail network evolved has been Irene D. Neu and George Rogers Taylor in The American Railroad Network, 1861-1890 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956), emphasizing that American railways were built to serve local needs or to serve the interests of rival commercial centers to capture trade in the hinterland. They argued that there was little incentive to create a common gauge and that the railroad network was disjointed and incomplete for decades until corporate consolidation and standard gauge agreements helped create more continuous systems in the 1880s and 1890s. This competitive rivalry explanation, however, misses the regional variation in gauge adoption that characterized the network growth in its early years. Douglas J. Puffert in "The Standardization of Track Gauge on North American Railways, 1830-1890," (The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 60, No. 4, Dec., 2000, pp. 933-960) found that "at the height of diversity during the 1860s" there were 9 different "regions" or network. He wanted to explain how certain gauges came to dominate particular regions. Puffert looked at "microlevel" where he found that "the process was path dependent, in that later outcomes depended on the specific course of preceding events rather than simply on such a priori factors as technology, tastes, or factor endowments." It turned out that the 4 feet 8.5 inch gauge was always adopted by more railroads than any other gauge but from late 1830s to 1860 the proportion of new mileage built in that gauge was steadily dropping, from 87 % to 44 %--overall the total proportion of this supposedly standard gauge fell from 80 % to 55 %. Puffert argued there were nine regional networks in this period and that the decade from 1855 to 1865 was the most diverse period in American rail development with only 17-18 % of the entire network reachable on a common gauge route without break. The spatial context of a railroad's development, it turned out, shaped decisions about gauge--railroads had every incentive to use the same gauge as the most proximate lines, not necessarily the majority gauge of the system as a whole. Railroad engineers focused on making their line compatible with those nearby, and followed the leading lines in their region.

Keywords

- Category: Language Analysis and Visualizations

- Topic: War

Related Documents

- Request for passes for African American railroad workers

- No. 1. Steam engines "Telegraph" and "O. A. Bull," Atlanta, Ga., 1864

- Boxcars with Refugees at Railroad, Atlanta, Ga., 1864

- Hospital Train from Chattanooga to Nashville

- General William T. Sherman at Fort No. 7, Atlanta, Ga., overlooking Chattanooga Railroad lines, 1864

- Burning the Railroad Bridge at Resaca, Georgia

- Fortified Railroad Bridge Across Cumberland River, Nashville, Tennessee, 1864

In a recent paper before the U. S. Army Command and Staff College, Christopher Gabel argued that Union commanders practiced a form of "Railroad Generalship" and in so doing structured their campaigns and their strategy around the railroads. Railroads increased the scale of operations, he points out, so much so that Sherman's managed to supply an army of 100,000 men and 35,000 animals over a single line of railway extending 473 miles from Louisville, Kentucky, to Atlanta. Without the rail his army would have required over 36,000 wagons and 220,000 mules. Other historians too have suggested the importance of the railroad in Civil War tactics and logistics, including John C. Clark Railroads in the Civil War: The Impact of Management on Victory and Defeat (Lousiana State University Press, 2001), George Edgar Turner, Victory Rode the Rails: The Strategic Place of Railroads in the Civil War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992, 1953), and Robert C. Black, The Railroads of the Confederacy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1952).

But "railroad generalship" in the Atlanta Campaign extended the reach of modern warfare far beyond the realm of logistics and supply. Just as railroad development did across the country decades earlier, the campaign became for Northern commanders a far-reaching attempt to reshape the social and physical environment of an entire region--the American South. To defeat the South Sherman thought he needed to master the region's complex nature, that is, to dominate, control, and comprehend its landscape, and its people. No one did this more effectively or thoroughly than Sherman, who, for his part, called forth geographical knowledge from twenty years earlier and assembled information on the railroads, distances, networks, topography, and characteristic of every local setting his army occupied. This intense geographic vision became the defining feature of his "railroad generalship."

Despite a war fought on a grand scale, made possible by the extensive railroad network, Union commanders in 1864 took a more intensive approach. The military reports of the Union Army commanders reveal the intensely local vision they held of the campaign and its structure around the railroads.