Google Lab’s Ngram viewer allows anyone to comb through over 5 million books for patterns and word trends in history. When Jean Baptiste Michel, et al., published their findings in “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books,” they used as an example the trend for the word “slavery” with its peak in the 1850s and again in the 1960s during the Civil Rights Movement. Last week, Robert K. Nelson in the New York Times Opinionator on “Of Monsters, Men — and Topic Modeling,” used the Richmond Daily Dispatch corpus from the Civil War to suggest the power of words to influence human ideas and events.

According to Nelson, “No historian has yet to display the patience and attention to detail to read through the more than 100,000 articles and nearly 24 million words of the wartime Dispatch, let alone conduct the sophisticated statistical analysis necessary to draw conclusions from the data.” Nelson proposes “an innovative text-mining technique called ‘topic modeling’ allows us to understand in far greater detail the arguments and appeals that were used throughout the war.”

Nelson is right, of course, that the scale of the problem for historians is significant and growing more so it seems with each passing day. Just taking the Richmond Daily Dispatch, my colleagues and I have discovered over 8,300 unique place names in the 4 years of the Civil War newspaper. These places names were mentioned over 292,000 times in that four-year span. Analyzing the geography of the war through even a single newspaper becomes impossible without computational tools. (We will release our geocoded Daily Dispatch next week at the National Endowment for the Humanities Digging into Data conference.)

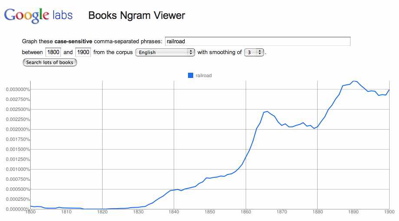

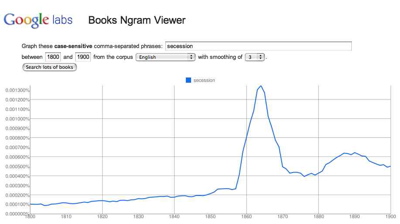

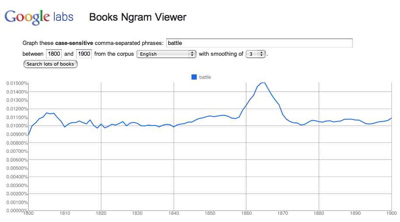

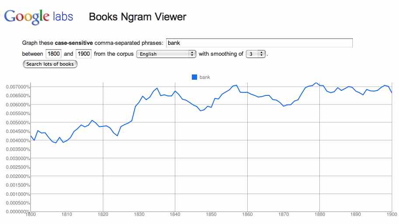

Now, Google Labs Ngram viewer allows us to crawl through millions of printed books, journals, and materials. A simple search in Google on the following terms turned up some surprising results:

slavery, bank, battle, railroad, cotton, secession, and Nebraska.

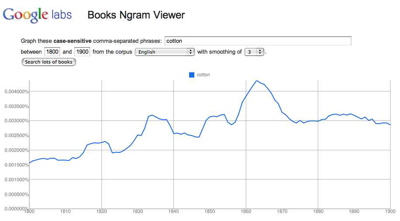

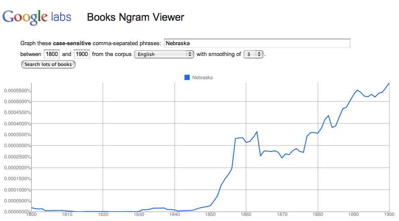

“Secession” appeared like a comet, flaming out in the course of the Confederate States of America. “Battle,” surprisingly, became more prevalent but only marginally. “Bank,” the subject of intense controversy in American politics from the 1830s, appears to have been remarkably steady in its frequency. “Nebraska,” a proxy for western expansion into the territories, spiked in the 1850s, unsurprisingly.

“Railroad” as a concept in American culture, society, economy, and politics, however, clearly spiked in period between 1850 and 1865. Despite researching and writing about the relationship between railroads and the coming and fighting of the Civil War, I was surprised (and pleased) at the sharpness, the apparent clarity of this result. Another aspect of NGram Viewer, it should be pointed out, is the anticipation we experience in waiting for the graph, and how the precision of its interface affects researchers. When a scholar has worked in the archives for years and then types in “railroad” or “cotton” into the box, he or she naturally experiences a sort of “uber-search” rush of adrenaline.

It is difficult to be sure exactly what these terms mean in the larger corpus of works in Google Books, but “slavery” and “railroad” and the Civil War were perhaps more deeply interconnected than historians have previously considered.

NGram Views:

|

Railroad:

|

|

Secession:

|

|

Battle:

|

|

Bank:

|

|

Cotton:

|

|

Nebraska:

|