Northern Expansion in the 1850s

- U. S. North Railroads, 1850

- U. S. North Railroads, 1855

- U. S. North Railroads, 1861

- Illinois Central Railroad Land Sales, March 1852 to December 1856

- All Sales from Illinois Secretary of State Database

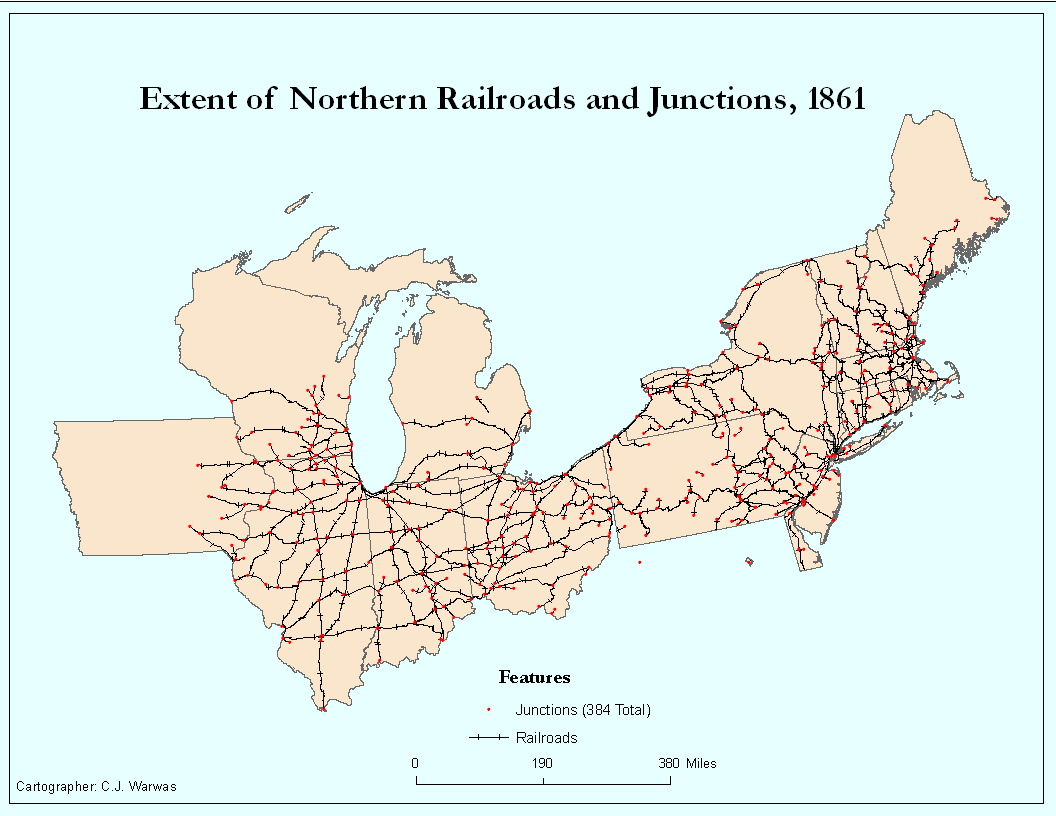

U. S. North Railroads, 1861

Keywords

- Category: Animations

- Category: Historical GIS Images

- Topic: Expansion

Related Documents

The transformation of Illinois was nothing less than explosive in these years. The Illinois Central advertised intensely and attracted settlers from England, Canada, Vermont, Germany, and Ireland. Large numbers came from Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, and New England. The town of West Urbana in Champaign County provided a useful example: it was a depot in 1854, then in two years it had 1,500 people and farm prices had increased 100 per cent. The county also grew between 1850 and 1860: improved acreage jumped from 23,000 to 170,000 acres, and the value of farm property skyrocketed from $478,000 to $5,178,800. Carbondale, another Illinois Central depot town, stood as a lonely, recently surveyed railroad stop in 1852, but in five years the place attracted over 1,200 residents. Cairo too increased its population in the 1850s, by a remarkable ten times.

Paul Gates suggested that 34,000 sales were made by the Illinois Central from 1854-1870 and these sales brought 100,000 new residents to the state (Paul Wallace Gates, The Illinois Central and Its Colonization Work, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1934, p. 250) Carlton Corliss argued that the modern advertisement campaign by the road was not in full effect until 1857 and that the federal alternate section land within the grant areas sold very rapidly at $2.50 an acre. The federal land office opened in August 1854 and the first two years sales went at a furious pace, according to Corliss 819,000 acres worth of land sold by 1856. (Carlton J. Corliss, Main Line of Mid-America: The Story of the Illinois Central, New York: Creative Age Press, 1950, p. 82) The Illinois Central land sales slowed in the Panic of 1857 and the loss of income threatened to undo the company's finances entirely.

The Illinois Central land grant, however, had shown how a free state might be settled rapidly. Iowa provided another example. In the years around 1856, moreover, the railroads brought formerly distant regions into unexpectedly close proximity--New England free labor, anti-slavery, and abolition advocates were so much nearer to Kansas in 1856 than ever before. Along the borders, including some of the fastest growing slaveholding counties in the South, slavery was no longer a distant threat to northerners but instead a visible presence three or four depot stops away. Slavery's strongholds were measurable in minutes on a railroad time table from places in the free North.