Map Inaccuracies in Railroad Sources

- Cram's 1879 Railroad Map of Nebraska, close up of Fort Kearney

- G. B. Colton's 1876 Map of Nebraska, close up of Burlington Railroad near Fort Kearney

- Phelps' Traveler's Guide 1850, close up showing Erie Railroad to Dunkirk, New York

- Nebraska Railroad Expansion, 1865-1886 Animation

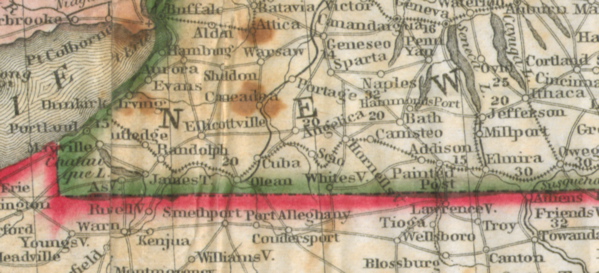

Phelps' Traveler's Guide 1850, close up showing Erie Railroad to Dunkirk, New York

Keywords

- Category: Historical GIS Images

- Topic: Expansion

Related Documents

In 2006-2007 our teams at the University of Nebraska and the University of Portsmouth began independently assembling sources to develop a GIS of the rail network in the 19th century United States. In Nebraska began close to home by tracing the year-by-year expansion of the rail network of the state between 1864 and 1880. This work encompassed the building of the Union Pacific Railroad, the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad, and the Fremont, Elkhorn Valley & Missouri Railroad. Our initial goal for the Nebraska data was to develop a method for capturing a national GIS of year by year rail growth in the U.S.

As a partnership between the University of Nebraska and the University of Portsmouth, we sought initially to combine GIS data at different scales, and recognized early on the difficulty of assembling and integrating GIS files. Because historical maps, such as the Rand & McNally series and other railroad atlases, often contained never completed roads and projected lines and towns, we needed to develop methods that could be checked against accurate historical sources. But we did not fully appreciate how challenging a national and regional GIS would be and just how many unresolved questions remained.

Here are two significant examples of map inaccuracies that have confronted our team and challenged our efforts to develop a national and regional scale GIS of the rail system.

1. The Burlington & Missouri River Railroad in Fort Kearney, Nebraska.

2. The Erie Railroad in western New York.

The 1850 map included in Phelps' Travelers Guide shows the Erie Railroad completed through to Dunkirk, New York. However, the Portsmouth team's GIS of depots and track line data show the Erie Railroad completed only to Hornellsville. Because the Portsmouth data is based on detailed examination of the railroad's annual reports, we discovered the discrepancy in the Phelps map. The Erie report for February 1851 indicates that the line was opened to Hornellsville in September 1850. By February 1851 another 51 miles were opened to Cuba, and by May 1851 the last 77 miles were opened to Dunkirk. The grading and masonry work on the roadbed to Dunkirk were, it turns out, completed during 1850, but the road was not opened for service over the last 128 miles until 1851. For readers of Phelps guide they could not have reached Dunkirk in 1850.

We found that digitizing historical maps and capturing line data from them resulted in wide variation and inaccuracies. Our experience led us to create a process that includes:

a.) working from the current Tiger line data on railroads as a base network--Railroads present before 1900 but abandoned before 1970 need to be added back in and we use a background of known hydrological and population features at the 1:100,000 scale with the historical sources as a guide to depots and line routes.

b.) using the extensive archival railroad record maps held in archives and assembling a base bibliography of these maps for references and chronological growth of the system--This provides scholars with a large online publication of relevant map resources on these railroads, including the collection of the Library of Congress railroad maps, as well as map sources at the Hagley Museum, Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania, the Newberry Library, the New York Public Library, the British Library, and the Nebraska State Historical Society.

c.) creating consistent and thorough metadata capture for each aspect of the GIS

d.) taking a scope of detail and resolution to all railroads of 10 miles or greater basis, subject to connectivity on a larger line.

e.) working toward as close to one year intervals as possible for the period 1830-1900.