Photographs and Images

All photographs and images produced for The Iron Way are copyrighted and may not be reproduced for sale or redistribution without permission of Yale University Press and the author. Original rights holders are indicated below. The images have been presented here in Zoomify and in the highest resolution possible to allow especially detailed investigation to identify individuals, features, and places.

*additional images not in original text

|

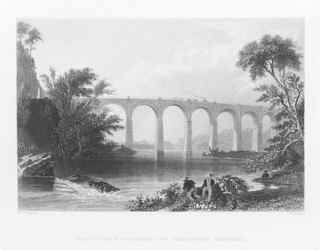

Figure 1: William H. Bartlett, Viaduct on the Baltimore and Washington Railroad, 1836. Completed in 1835, the viaduct on the Baltimore & Ohio’s Washington branch was an engineering wonder--the first multispan stone bridge built on a curve. Designed by Benjamin Latrobe, the bridge appeared to defy conventional limits of speed and gravity. (Courtesy of the author) |

|

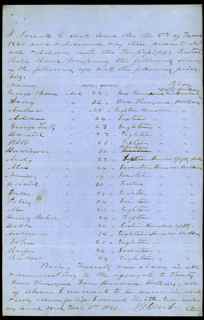

Figure 2: Receipt for sale of slaves to the Mississippi Central Railroad, March 5, 1860. Railroad companies in the South routinely bought slaves in the 1840s and 1850s, often purchasing thirty to fifty at a time. The “asset” would be carried on the company’s annual balance sheet, often listed as “the negro account.” (Courtesy of the Newberry Library) |

| (Restricted) | Figure 3: Samuel J. Miller, Frederick Douglass, 1847–52. Cased half-plate daguerreotype (plate: 14 × 10.6 cm), Art Institute of Chicago. Writing an open letter “To My Old Master” in 1848 in his newspaper, Douglass explained his escape this way: “The probabilities, so far as I could by reason determine them, were stoutly against the undertaking [his escape]. . . . It was like going to war without weapons. . . . One in whom I had confided, and who had promised me assistance, appalled by fear at the trial hour, deserted me, thus leaving the responsibility of success or failure solely with myself. You, sir, can never know my feelings.” (Major Acquisitions Centennial Endowment, 1996.433, The Art Institute of Chicago.Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago) |

|

Figure 4: Phelps Traveler’s Guide, 1850. This pocket atlas listed over 700 railroads, steamship lines, and canals in the United States and their routes of service, state by state. Frederick Douglass probably consulted a rudimentary timetable in the Baltimore newspaper or one posted at the depot for the Baltimore to Philadelphia route, described here twelve years after Douglass made his escape from slavery on the Philadelphia, Wilmington, & Baltimore Railroad. (Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries) |

| (Restricted) | Figure 5: Edward Beyer, "The High Bridge near Farmville," The Album of Virginia, 1858. In the 1850s southern railroads built some of the longest tunnels and bridges in the United States with some of the best engineering talent that available. They used slave labor almost exclusively. (Courtesy of the Library of Virginia) |

|

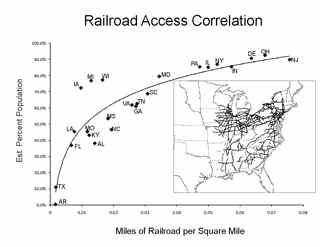

Figure 6: Railroad access trend line by state, 1861. Using a fifteen-mile buffer around the railroad networks for each state in 1861, and an algorithm to distribute a county’s population across the landscape, this estimate of the percentage of county residents who had access to the railroad depots shows the South’s advances in the 1850s. The addition of more railroad miles reached a point of diminishing returns in every state. (Graph and map by C. J. Warwas, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities) |

|

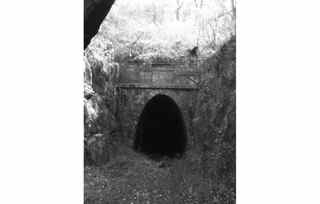

Figure 7: The ruins of the Blue Ridge Tunnel, as it appears today. The Blue Ridge Railroad and Blue Ridge Tunnel were built by the state’s Board of Public Works. When the railroad company’s chief engineer, Claudius Crozet, requested slave labor, the board had to decide whether the state should purchase slaves for the project. The tunnel has long since been abandoned, but the brick and stonework is the original, much of it slave-built. (Courtesy of Jean Bauer) |

|

Figure 8: Andrew J. Russell, Slave Pen, Alexandria, Virginia, c. 1861–1865. Railroads transformed the way slaves were sold and transported. The slave market boomed in the 1850s with the expansion of railroad construction across the South, and traders moved along the network using the telegraph to make and finalize deals. This slave trader was positioned strategically one block from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad depot. (Lot 11486-H, No. 10, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

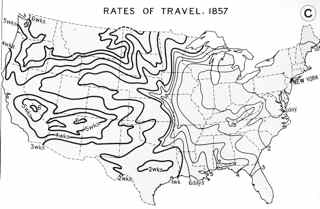

Figure 9: Charles O. Paullin, “Map of the Rates of Travel in 1857 from New York City,” in Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States. Paullin’s map remains one of the most widely reproduced visualizations of the social changes brought by the railroad. While New York, as the largest U.S. city, increased in importance in the 1850s, other regional hubs, such as Baltimore, Maryland, and Charleston, South Carolina, competed for supremacy and status on the rapidly advancing railroad network. (Washington, D.C./New York: Carnegie Institution of Washington and the American Geographical Society of New York, 1932) |

|

Figure 10: Boston & Worcester Railroad, 1862 Time Table. (Library of Congress) The railroad timetable was an astonishingly complex innovation. At first, time tables were printed on small cards because local railroads, such as the Boston & Worcester, made just one or two runs a day over a short distance. But the 1850s marked a major shift as hundreds of new junctions came on line in the Midwest and South. Railroads in the 1850s operated primarily as passenger lines, and time tables for longer lines became increasingly intricate. |

|

Figure 11: Part of the Illinois Central Depot, Chicago (Harper’s Weekly, September 10, 1859). “The awakening of the great Northwestern country has commenced at Chicago,” Harper’s reported. (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries) |

|

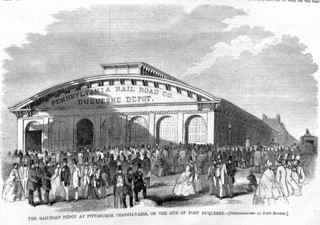

Figure 12: The railroad depot at Pittsburgh (Harper’s Weekly, December 4, 1858). Pittsburgh celebrated 100 years since Fort Duquesne was captured from the French--the railroad depot stood on the site of the old fort, a symbol of the city’s modernity. By 1861 Pennsylvania possessed over 500 depots, so many that 85 percent of the state’s population lived within fifteen miles of a depot. (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries) |

|

Figure 13: Railroad Workers, 1850s. Few original images remain of railroad workers in the 1850s, especially of construction crews, whether free labor or enslaved. Northern railroad companies employed thousands of men on their payrolls in a dizzying array of occupations. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 14: Richard Cobden, a leading Liberal in Parliament, was also invested in the Illinois Central Railroad. He took two major trips to the United States, first in 1835 and again in 1859. During his first trip he traveled on railroads for a total of just ninety miles, from Lowell, Mass., to Boston, and then to Providence, R.I. On his second trip, twenty-four years later, he traveled 4,000 miles on American railroads. (Image from John Bright and James E. Thorold Rogers, eds., Speeches on Questions of Public Policy, Vol. I (London: MacMillan and Co., 1870]) |

|

Figure 15: Passenger Station of the Little Miami Road. Railroad completion celebrations became highly orchestrated events. They served local, regional, and national purposes simultaneously. And they often featured an excursion trip over the line with artists, newspaper editors, political leaders, and railroad officials. Stops along the way showed off the beautiful, large, and bustling station buildings and depots in the major urban places on the route. (“Passenger Station of the Little Miami Road,” from William Prescott Smith, The Book of the Great Railway Celebrations of 1857) |

|

Figure 16: Baltimore & Ohio Railroad artist’s excursion, 1858. Following its 1857 grand banquet, the B & O hosted an artists’ excursion in 1858 to show off its dramatic vistas and massive tunnels. The men and women took turns riding precariously on the cowcatcher, Harper’s Weekly reported, to get a “better view of the grand scenes which were opening before and around them . . . such was the confidence felt in the steadiness and docility of the mighty steed.” (Z24.485 Courtesy of Maryland Historical Society) |

|

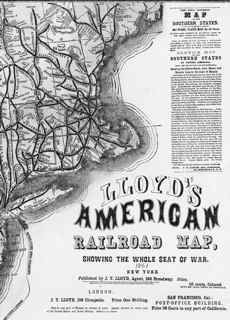

Figure 17: "The Seat of War in Eastern Virginia," New York Daily Tribune, New York, May 6, 1862. Railroad atlas and newspaper publishers in New York and Philadelphia possessed vital information on the South’s network of junctions, towns, depots, and rails. Newspapers began printing front page maps for the first time in the war to help readers understand the complex geography of the Confederacy. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 18: Columbiad guns of the Confederate water battery at Warrington, Fla., near Pensacola, February 1861. With the railroad to Pensacola under construction and finally completed in May, the Confederates could move large guns and troops more quickly to the coast. (National Archives and Records Administration) |

|

Figure 19: Ephraim C. Dawes’ Sketch Map of His March, November 10, 1863. (Courtesy of The Newberry Library) An officer in the 53rd Ohio Infantry, Dawes sent this map to his sister after his unit marched twenty-three miles one day and thirteen miles another. Working their way along the railroads in southern Tennessee, the 53rd Ohio had little access to mail and only received “the mildest rumors thro the country.” Dawes’ map, like countless others, was an artifact of his personal experience, showing the compressed geography of his war and his events. |

|

Figure 20: Electioneering in Mississippi: “Rough Riding Down South,” Harper’s New Monthly, June 1862. Even in the second year of the Civil War, Harper’s middle-class magazine was producing travel essays on the South for its northern readers, in this case depicting a trip through the region in the early 1850s. Despite the South’s growth in that decade, the piece featured no railroads, instead preferring to depict a rural, backward, isolated, and unkempt region. |

|

Figure 21: Hanover Junction, 1863. (Library of Congress) Northern railroad stations became places to gather for news and information. President Abraham Lincoln passed through Hanover Junction in November 1863 on his way to Gettysburg for the opening of the national cemetery. Crowds gathered to meet the president. |

|

Figure 22: Ephraim C. Dawes, 1863. Dawes fought in the Battle of Shiloh, then protected the railroads in Tennessee with the 53rd Ohio. He was promoted to major of the regiment on January 26, 1863. (Courtesy of the Ohio State Historical Society) |

|

Figure 23: Cumberland Landing, Federal Encampment on the Pamunkey River, Va., May 1862. Union soldiers came into the South by steamer and train in the first year of the war. They closely observed the landscape, assessing and comparing it to their northern communities. (Library of Congress) |

|

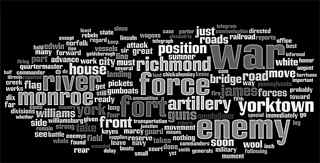

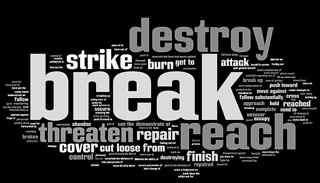

Figure 24: Keywords appearing in all Union officers’ correspondence in the 1862 Peninsular Campaign. (the larger the word, the more often it appeared in their writings) Compiled from U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Gettysburg, Pa.: National Historical Society, c. 1971–1972), Vol. 11 (Part III), 1–384. (Voyeur Tools [copyright 2009] Steffan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell, v. 1.0; graph by Trevor Munoz and the author [September 2009]. This image was generated using Wordle, under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.) |

|

Figure 25: Savage’s Station, headquarters of General George B. McClellan, June 27, 1862. McClellan used the Richmond & York River Railroad to position his massive Army of the Potomac just a few miles from Richmond. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 26: Ruins at Manassas Junction, March 1862. Numerous railroad hubs in the Confederacy became sites of repeated fighting, both large- and small-scale. Here, the ruins were the work of the Confederate Army as it abandoned its forward position in northern Virginia to protect Richmond. (National Archives and Records Administration) |

|

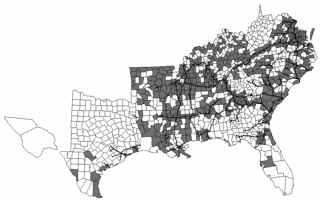

Figure 27: Railroads and war zone counties, 1861–1865. If the presence of the Union army and/or a battle constituted a war zone, then only in Virginia did the Civil War’s destruction touch the majority of counties. Vast sections of the South remained out of the war zone, but over the course of the war destruction tended to follow closely along the pathways of the major lines of communication and transportation. From Paul F. Paskoff, “Measures of War: A Quantitative Examination of the Civil War’s Destructiveness in the Confederacy,” Civil War History, Vol. 54, No. 1 (March 2008). (Reproduced with permission of Paul F. Paskoff) |

|

Figure 28: Alfred R. Waud, A Guerrilla, 1862. When guerrillas attacked Union forces, the northern public was outraged. Confederate guerrillas and partisan rangers attacked the railroad and telegraph systems, opening up the war to civilians and exposing the remorseless nature of the national conflict. Their activities played a central role in the war. (Library of Congress) |

|

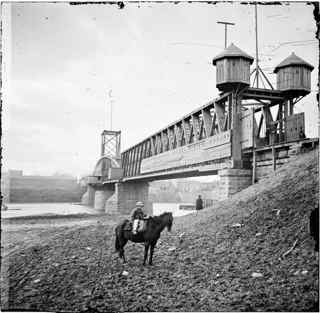

Figure 29: George N. Barnard, Fortified Railroad Bridge Across Cumberland River, Nashville, Tennessee, 1864. Confederate guerrilla forces, often operating as regular cavalry units, attacked Union-controlled railroad lines. They shot into trains, destroyed tracks, took prisoners, killed Union soldiers, and burned bridges. Union commanders responded by developing block houses and fortified bridges to protect the vulnerable lines, equipping trains with special armor, recruiting loyal local citizens to ferret out guerrillas, and dispatching special counterinsurgency cavalry units to track down the Confederate guerrillas. (LC-B811-2642, Lot 4177, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 30: Pickets of the 1st Louisiana “Native Guard” Guarding the New Orleans, Opelousas and Great Western Railroad. United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) recruiters in 1863 fanned out along the railroads, especially in Tennessee, stopping at depots along the route to sign up soldiers. Over 180,000 black men volunteered and enlisted for service in the U.S.C.T. Both white regiments and U.S.C.T. units found themselves guarding railroads and watching for guerrillas. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, March 7, 1863, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries) |

|

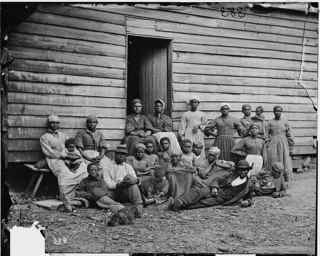

Figure 31: Contrabands at Cumberland Landing, Virginia, May 1862. In the Peninsular Campaign, Federal forces encountered thousands former slaves who sought freedom and work in the Union army camps. Even if slaves fled slavery, their status was unclear in the first year of the war. In July 1862 Congress declared such refugees from slavery “forever and henceforth free.” (Library of Congress) |

|

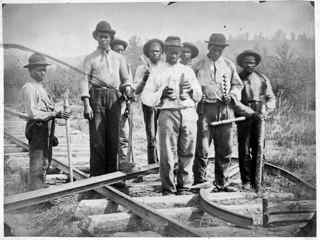

Figure 32: Andrew J. Russell, African American Laborers on the U.S. Military Railroad in Northern Virginia, c. 1862 or 1863. From the beginning of the Civil War, African Americans worked on the railroads, transferring their labor to the Union cause. (Lot 9209, No. 49a, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 33: African American wood choppers’ hut on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad. Black men, many of them formerly enslaved on the South’s railroads, chopped timber for railroad ties, bridges, and fuel for the U.S. Military Railroads. Stationed at remote camps, such as this, they also faced the constant danger of Confederate partisan and guerrilla raids. (National Archives and Records Administration) |

| (Restricted) | Figure 34: Lionel Nathan de Rothschild was one of a handful of powerful transatlantic bankers who emerged with the marketing of U.S. and state bonds, railroad securities, and agricultural commodities in Europe. Rothschild held antislavery convictions but expected the Confederacy to become independent. The firm’s southern businesses collapsed in the Civil War, and the transatlantic bankers’ pragmatism and neutrality effectively isolated the Confederacy. (Reproduced with the permission of the Rothschild Archive) |

|

Figure 35: Wreck of blockade runner, Sullivan’s Island, S.C. Blockade runners became increasingly sophisticated, taking advantage of the latest technological innovations to achieve maximum speed. For Confederates, the blockade--combined with shortsighted Confederate policies of self-reliance--slowed time and cut off communication with the world of nations, damaging Confederate transatlantic ties and claims of modern progress. (Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 36: George Barnard, Boxcars with Refugees at Railroad, Atlanta, Ga., 1864. With the capture of Atlanta, General William T. Sherman’s army seized an important rail hub for the Confederacy. This image of refugees and African Americans, sitting on rail cars with their possessions, indicates the massive displacement that came with the war. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 37: General William T. Sherman at Fort No. 7, Atlanta, Ga., overlooking Chattanooga Railroad lines, 1864. Sherman recognized the importance and vulnerability of railroad corridors. In September 1862 Sherman ordered an expedition to “destroy” the town of Randolph, Tennessee, because guerrillas had fired on Union steamships from the banks of the Mississippi River. In 1864 he adopted similarly hard measures to protect the railroads during his Atlanta Campaign. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 38: Keywords appearing in General William T. Sherman’s correspondence in the Atlanta Campaign of 1864. (the larger the word, the more often it appeared in his writings) Compiled from U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Gettysburg, Pa.: National Historical Society, c. 1971–1972), Vol. 38 (Parts IV and V), including all of Sherman’s letters in these volumes. (Voyeur Tools [copyright 2009] Steffan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell, v. 1.0; graph by Trevor Munoz and the author [September 2009]. This image was generated using Wordle, under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.) |

|

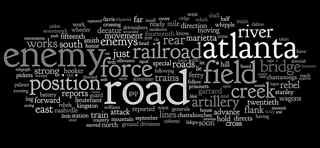

Figure 39: Keywords appearing in all Union commanders’ correspondence in the Atlanta Campaign of 1864. (the larger the word, the more often it appeared in their writings) Compiled from U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Gettysburg, Pa.: National Historical Society, c. 1971–1972), Vol. 38 (Parts IV and V), including all Union command correspondence. (Voyeur Tools [copyright 2009] Steffan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell, v. 1.0; graph by Trevor Munoz and the author [September 2009]. This image was generated using Wordle, under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.) |

|

Figure 40: No. 1. Steam engines “Telegraph” and “O. A. Bull” remained in position amid the ruins of a Confederate roundhouse in Atlanta in 1864. The South possessed some of the most beautiful depots and railroad facilities in the nation in 1861. Sherman’s campaigns sought to dismantle the Confederate railroad system and in so doing deny any claim to modernity and progress. African American workers stand atop the old Georgia Railroad flatcar. (George N. Barnard, LC-DIG-ppmsca-18960, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

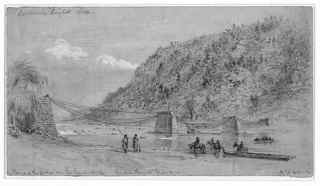

Figure 41: Alfred R. Waud, Ruins of the Bridge over the Shenandoah River, Loudon Heights Beyond, 1864. The partisan war in Loudon County, Virginia, turned especially violent in the fall of 1864. Confederate forces under John S. Mosby captured and killed Union soldiers in retaliation for the burning of civilian homes, and Union general George A. Custer responded by hanging seven of Mosby’s men. Then, on November 6, 1864, Mosby executed several more Union soldiers in response. The fighting took place along the Manassas Gap Railroad line and its bridges. (Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 42: Ephraim C. and his wife Francis Dawes, 1883. While a member of the 53rd Ohio Volunteers during the Civil War, Dawes was wounded in the face at the Battle of Dallas in May 1864 during the Atlanta Campaign and was grossly disfigured as a result. A prolific writer of regimental and war histories after the conflict, Dawes was fitted with a prosthetic jaw with lower teeth and adopted a full beard to cover his wounds. Lithographers and publishers used his 1863 likeness for his publications. (Courtesy of the Ohio State Historical Society) |

|

Figure 43: Andrew J. Russell, Military Railroad Bridge over Potomac Creek, 1864. This bridge was destroyed and rebuilt several times. In May 1862 General Irwin McDowell employed hundreds of contraband laborers, who replaced the bridge in nine days. Here, in May 1864, the U.S. Military Railroads, again with large numbers of black freedmen, constructed the bridge in forty hours. Photographs such as this one indicated the complexity, cost, and scale of the bridges across many of the South’s rivers and also conveyed the precarious, and sublime, ways the railroad was thought to defy nature. (Lot 4336, No. 37, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

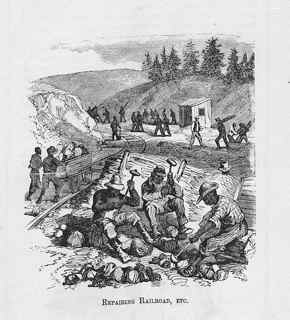

Figure 44: Repairing Railroad, Etc. The U.S. Military Railroads rebuilt the South’s railroads in the closing months of the war. African American railroad workers cut timber, broke rock, and hauled gravel for the grading. Their experience on the railroads as trackmen and laborers, as well as firemen and brakemen, continued after the war. In 1880 over 50 percent of all railroad workers in Virginia were black; in Pennsylvania, by contrast, railroad workers were almost uniformly white. (From Report of Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army, in North Carolina in the Spring of 1862 After the Battle of New Bern; Courtesy Texas A & M University Libraries) |

|

Figure 45: Andrew J. Russell, Bird’s Eye View of Machine Shops, with East Yard of Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Alexandria, Va., [1861-1865] In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, African Americans seized the opportunity to work and to travel. Visible just to the left of the railroad shop smokestack and roundhouse stood the old Price and Birch “Slave Pen” at 1315 Duke Street. (Lot 11486-C, No. 2, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 46: Andrew J. Russell, “Long Bridge” over the Potomac River, 1864. The original footbridge across the Potomac was replaced with this railroad bridge in 1864 by the U.S. Military Railroads, connecting Washington, D.C., with the army’s growing camps, hospitals, and defenses near Alexandria, Virginia. (Lot 11486-E, No. 9, Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress) |

|

Figure 47: Long Bridge, 2010. When Kate Brown crossed the Potomac River on this bridge in 1868 and was forcibly removed from the ladies’ car in Virginia, the Washington Monument was only half-completed. Brown’s work at the U.S. Capitol placed her in contact with powerful Republican Party lawyers and politicians. Her lawsuit against the company went to the U.S. Supreme Court five years later. (Courtesy of Margaret Konkel) |

|

Figure 48: Andrew J. Russell, Engineers Camp, Weber Canyon, the Union Pacific Railroad, 1868. This photograph captured part of Samuel B. Reed’s team of surveyors for the Union Pacific. Involved in every stage of the construction, Reed was pressed in the summer and fall of 1868 by financier Thomas C. Durant to cut corners on the engineering in Weber Canyon in northern Utah. In early 1869 Reed wrote his wife, Jennie, that the Union Pacific had “squandered uselessly” “immense amounts of money.” One month before the Union Pacific’s completion, the New York Times called its construction “one of the most monstrous frauds that was ever perpetrated upon any Government.” (Courtesy of Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries) |

|

Figure 49: Completion of the Pacific Railroad, Harper’s Weekly, May 29, 1869. This image was a metaphor for where the nation was going, although it said little about where the nation had been. Created by Alfred R. Waud, one of the most prolific Civil War sketch artists and lithographers, the image suggested a national tapestry of progress. Far from binding the nation, railroads and the culture that developed around them had been one of the root causes of discord and division. (University of Nebraska-Lincoln Libraries) |